Bubblewrap is the sandboxing technology behind Flatpak. It uses Linux namespaces to isolate processes from the rest of your system - limiting filesystem access, network capabilities, and more. It’s powerful stuff. The problem is that actually using it requires memorizing dozens of flags and getting the incantation exactly right. One wrong flag and your sandbox either doesn’t work or is too restrictive to be useful.

bui is an attempt to fix this. It’s beta, but it’s simple - it mainly just generates a bubblewrap command based on your choices and, if you’re happy, runs it. You can save working configurations as profiles and create “managed sandboxes” that permanently sandbox applications with a wrapper script. It also supports optional network filtering via pasta and, if configured, a lightweight DNS proxy.

Why a TUI?

Raw bubblewrap requires you to specify every bind mount, every environment variable, every capability as command-line flags. A typical bwrap command looks like this:

bwrap --ro-bind /usr /usr --ro-bind /lib /lib --ro-bind /lib64 /lib64 \

--ro-bind /bin /bin --ro-bind /etc /etc --proc /proc --dev /dev \

--tmpfs /tmp --unshare-all --share-net --die-with-parent \

--bind ~/.config/myapp ~/.config/myapp -- /usr/bin/myapp

Miss a bind and the app crashes. Add too many and your sandbox is pointless. Much easier to just browse the filesystem and toggle paths on and off, which is what the TUI gives you - no GUI dependencies, works over SSH, and you can inspect the generated command before running it.

Why not firejail? Firejail is setuid root, which means a larger attack surface - and it’s had security vulnerabilities in the past. Bubblewrap is more minimal: it’s the same sandboxing primitive that Flatpak uses, with a smaller codebase and less to go wrong. The tradeoff is that bwrap gives you nothing out of the box - hence bui.

Why Not Docker/Podman?

Containers solve a different problem. They need images, layers, storage drivers, and (for Docker) a daemon running. That’s a lot of machinery when all you want is to stop npm start from reading your SSH keys. With bubblewrap, you run your actual installed programs - no need to rebuild or find container images for every tool you want to sandbox. Your apps still get access to X11/Wayland, sound, and GPU without elaborate bind mount wizardry, and you can sandbox a single command in an existing shell session rather than committing to a whole container. Containers are great for what they’re designed for; this isn’t that.

Here are four things I use it for.

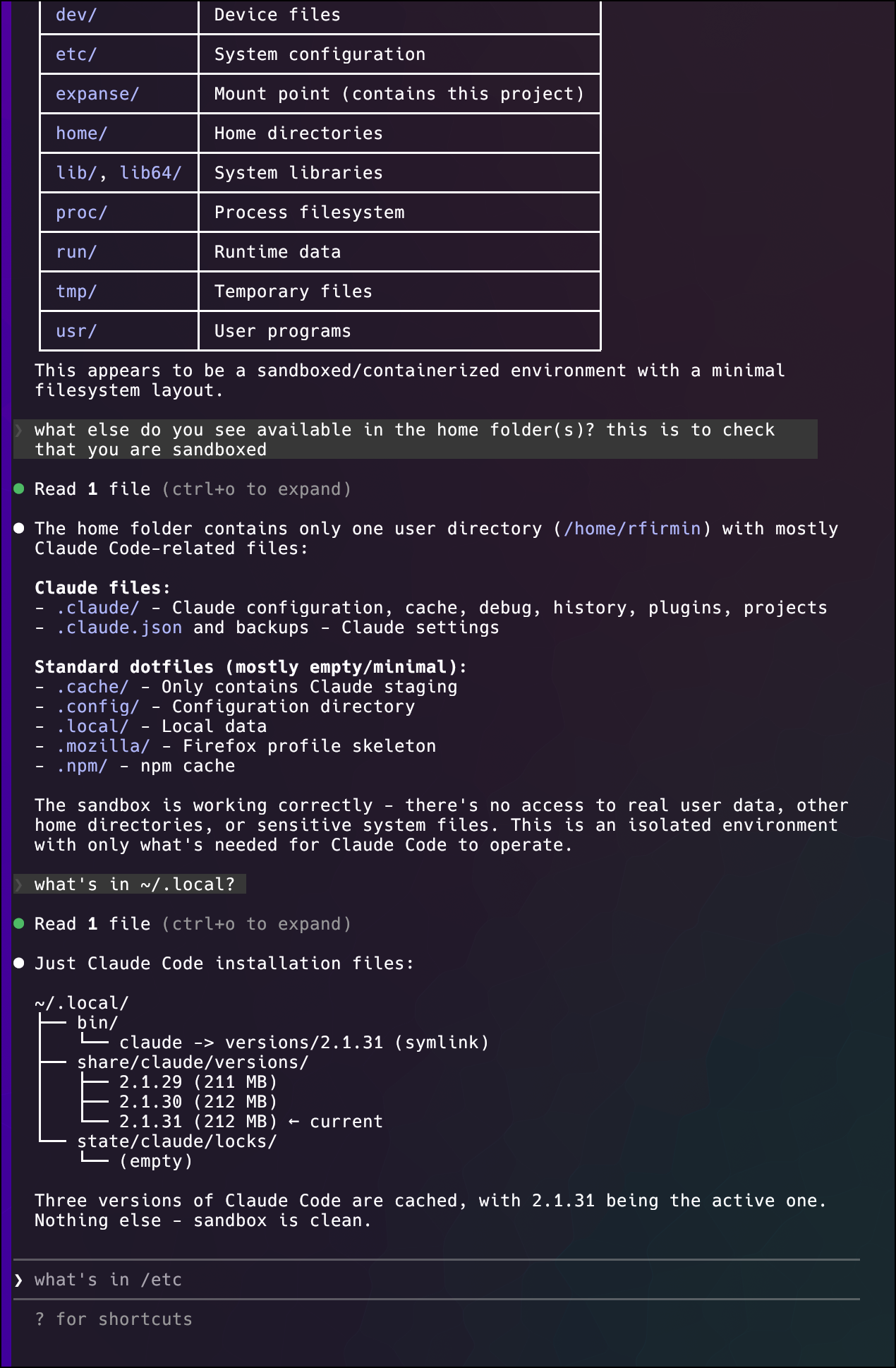

Sandboxing an AI Agent

I run Claude Code to work on projects, but it has carte blanche to execute shell commands. (Of course the agent has a permission model, but while I don’t wish to throw stones from my house of glass over here, Anthropic haven’t exactly been on a quality tear of late…some extra guardrails are useful.)

bui -- claude

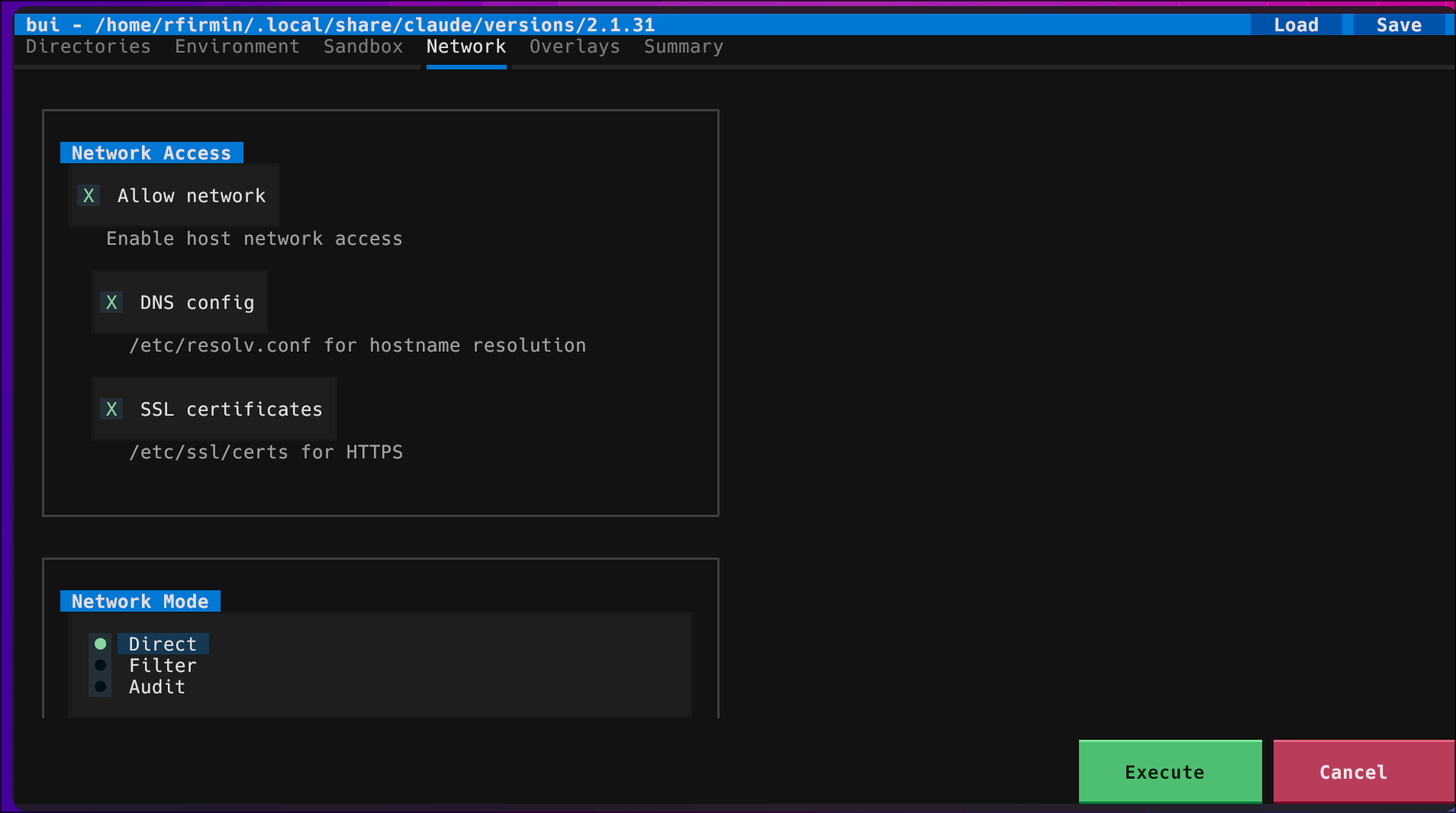

The TUI opens. I click to the network tab, allow network, and press enter to execute. The defaults are moderately locked down. The current working directory is mounted readonly, as is the directory containing the binary and several non-sensitive and generally needed system paths. Host processes and shared memory are isolated. Because I didn’t enable network filtering, it shares the network namespace with localhost. (If that’s not good enough, everything is of course configurable.)

The sandbox persists for the session; Claude can do its thing within the boundaries I set, and if something goes wrong, the blast radius is limited.

Installing npm Packages Safely

Installing global npm packages means running arbitrary code during install. Preinstall scripts, postinstall scripts, native compilation - any of these could be compromised, and npm’s track record here is not great (remember event-stream?).

bui includes an untrusted profile that isolates your home directory and makes system paths read-only:

bui --profile untrusted --sandbox vercel \

--bind $(dirname $(which npm)) \

--bind-env 'NPM_CONFIG_PREFIX=/home/sandbox/.npm-global' \

-- npm install -g vercel

The --sandbox flag creates a named, persistent sandbox - unlike a bare bui session that disappears when you exit, this one sticks around. The Vercel CLI gets installed into the sandbox’s own home directory, and the install scripts can’t touch your real one. If one of the dependencies is compromised, your system stays clean.

Then make it convenient:

bui --sandbox vercel --install

This creates a wrapper so you can just run vercel normally from your shell. It auto-sandboxes every time. (And, if you ever need to loosen or tighten the sandbox, you can clone the “untrusted” profile in the TUI and point the wrapper at your new one.)

curl | bash

Installing Claude Code via the recommended method means piping a URL to bash. That script downloads binaries, modifies your shell config, and runs arbitrary code. You’re trusting every hop between you and that URL.

bui --profile untrusted --sandbox claude \

-- 'curl -fsSL https://claude.ai/install.sh | bash'

The install script runs in a sandbox. It can write to its sandboxed home directory but can’t touch your real files, shell config, or anything else.

Then:

bui --sandbox claude --install

Now claude works normally from your shell, but it’s always sandboxed. The same pattern works for most curl|bash installers.

Running npm Apps

Third-party Node apps come with hundreds of dependencies, and every one of them is a potential ua-parser-js or node-ipc waiting to happen.

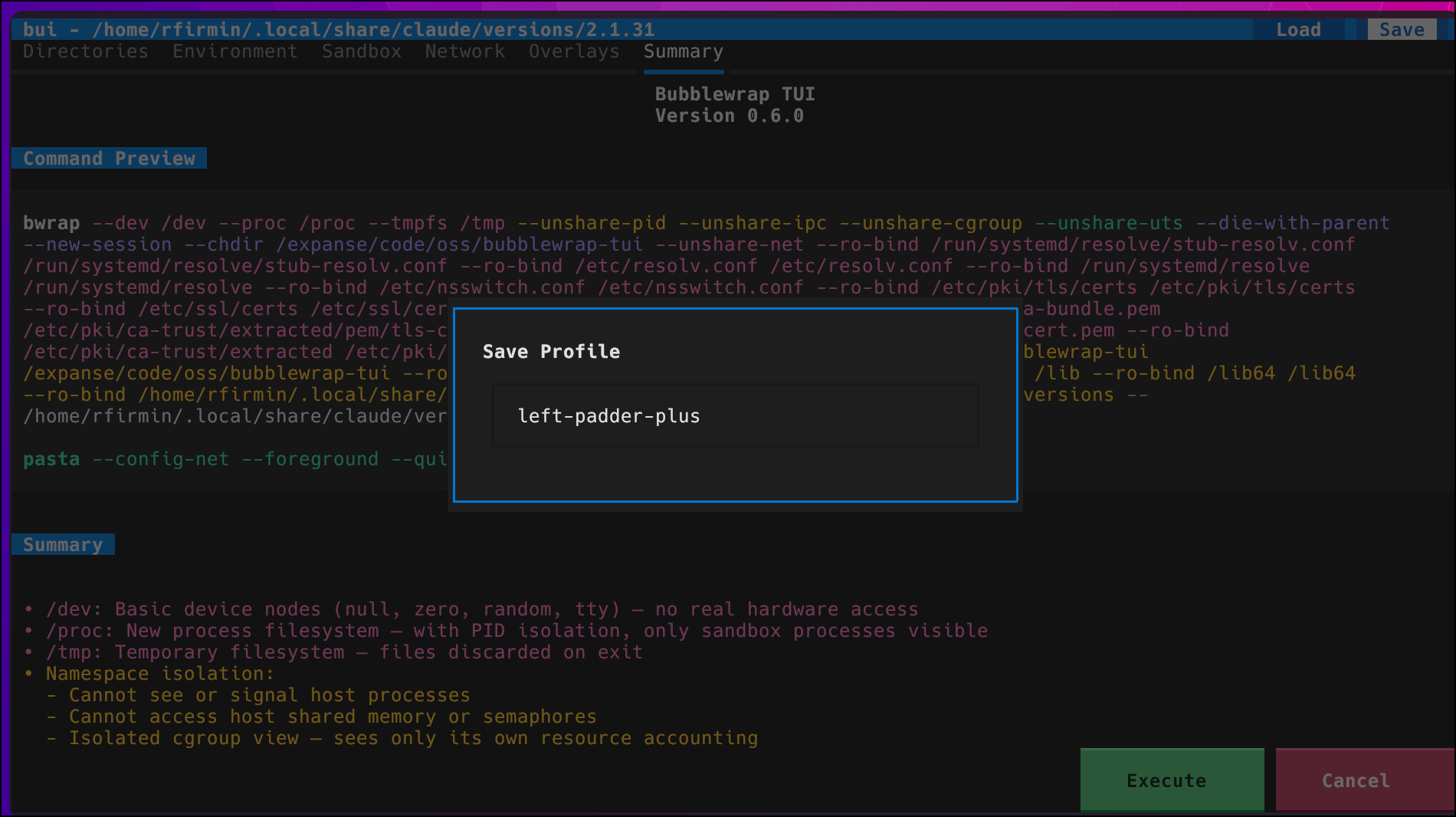

Create a profile via the TUI:

bui -- npm start

Configure the sandbox interactively: the app gets access to its own directory, maybe a specific port, and nothing else. Save the configuration as a profile (e.g., “left-padder-plus”).

Run with your saved profile:

bui --profile left-padder-plus -- npm start

A compromised package can’t access your SSH keys, browser data, AWS credentials, or anything outside the sandbox.

What Doesn’t Work

The sandbox can run as root (UID 0) - that’s even the default - but bui’s overlays are tmpfs-backed, meaning writes go to RAM and are discarded when the sandbox exits. That’s the whole point for isolating untrusted code. System package managers scatter writes across /usr, /etc, /var, /lib, and other directories; you’d have to set up persistent overlays for all of them, and there’s no way to merge those changes back into the real filesystem. (Flatpak sidesteps this by using fuse-overlayfs with persistent upper layers and shipping complete runtimes via OSTree rather than overlaying host directories.) If you want to test-drive a system package you don’t trust, use a container or a VM. That’s actually the problem they’re designed for.

Where bui shines is everything you run as yourself - npm packages, curl|bash installers, random binaries, AI agents with shell access. The stuff that’s already running with your full permissions and could be rifling through your home directory right now.

Getting Started

bui is on GitHub. It requires Linux, bubblewrap, and uv.

Don’t trust your life savings to this (yet) - there are only a handful of active users (remember kids, obscurity is the best kind of security), the code has not been independently audited, and there’s plenty of refactoring left to do from the initial weekend viberun (although, a lot of cleanup has been done). But, it’s convenient to use, and provides a way to use bubblewrap that would otherwise be cumbersome.

Yes, it’s elephants all the way down - you’re trusting a chunk of Python to set up your sandbox. The mitigating factor is that 99% of the actual isolation is done by bubblewrap and pasta, which are well-established and packaged by major distros. The remaining 1% is the optional DNS proxy, which only comes into play if you use hostname filtering. The ultimate goal would be to get bui itself to the quality bar where it could be submitted to distro package managers. If you’d like to help with that, I welcome PRs, bug reports, and feature requests.