Road engineers in Costa Rica do not worry about snow and ice. Whereas highway builders in the US might dynamite a chunk of a mountain to provide a road that maintains a reasonable gradient as it climbs, the road engineers of the tropics are happy to run straight upslope if there’s no good alternative. Asphalt was laid surprisingly recently on some relatively important routes; the Costanera, for example, which is the coastal “highway” that connects Jaco to Paso Canoas at the Panamanian border, was only paved in the early 2000s. Old timer gringos talk of having to ford rivers in their trusty land cruisers in the bad old days of the late 90s, with teams of oxen standing by at either side of the river crossing to pull cars up the banks and back to the bumpy dirt roads.

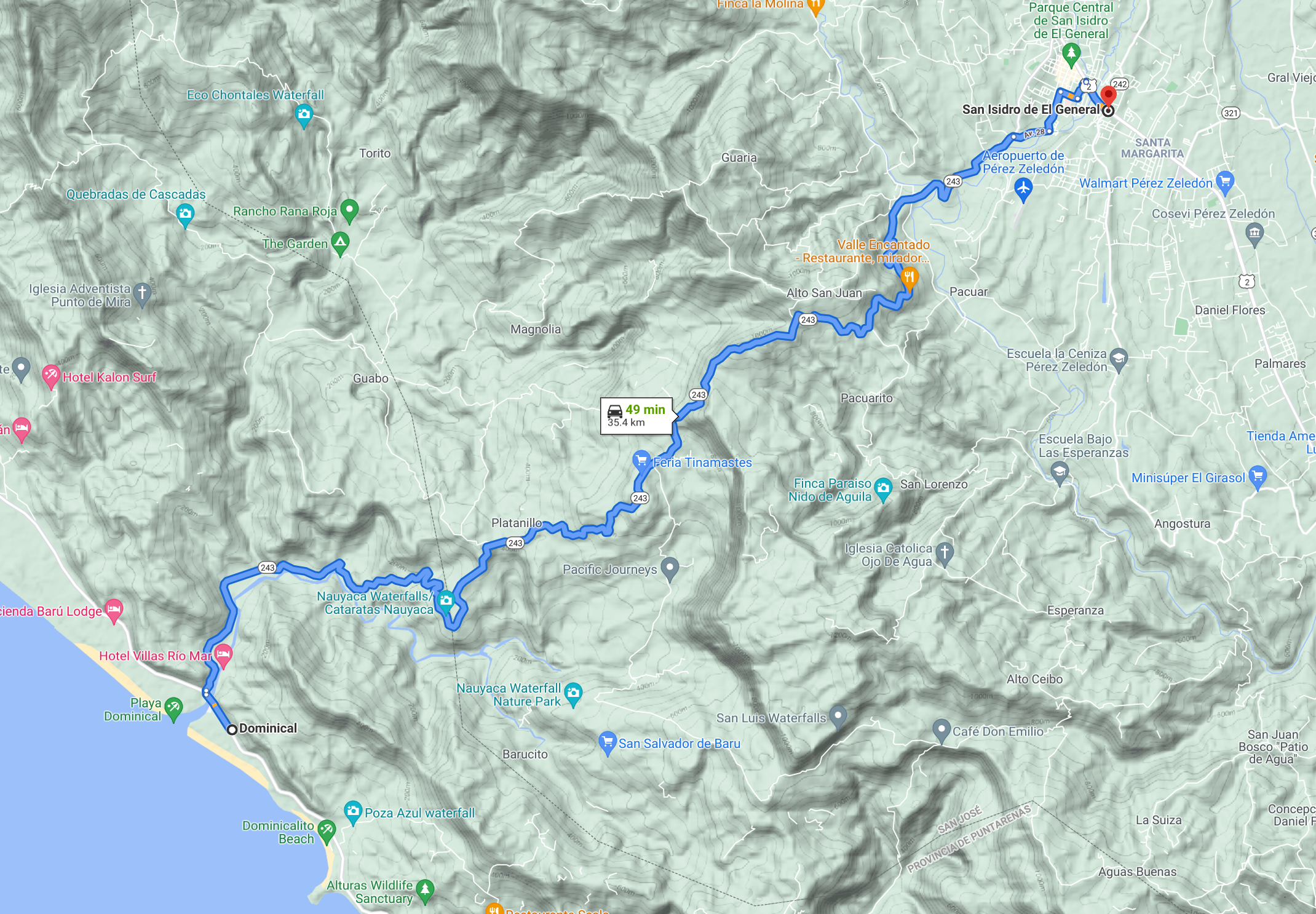

The main road from the Costa Ballena to San Isidro has a generous share of aggressive slopes as it climbs from sea level to breach a 1000m ridge before descending into the elevated valley surrounding the city. The road is only 35km, but if you get stuck behind a diesel truck (or series of trucks) on the uphill segment, it can easily take an hour to drive, as the shuddering engines struggle to do much more than 20km/h against the inclines; passing opportunities are rare, and the stream of traffic coming in the other direction is regular enough that many of the straights are spoiled. Local machos in latam styled pickups will sometimes blast past a half dozen cars and the leading truck in the narrow window leading up to a hairpin. It was in such a succession of truck led caravans that we found ourselves at 9AM one fine friday in dry season, as we began an expedition to drive la esposa’s car over the border and into Panama.

Tourist visas in Costa Rica are good for three months, after which (if you wish to continue being permitted to drive on your US license) you must leave and re-enter the country to get an updated entry date in your passport. The process to obtain temporary residency (thus allowing you to avoid such shenanigans) isn’t particularly hard, but the wheels of such bureaucracy tend to run slowly, and in our case the process had been stretched both by California’s sullen agents of paperwork taking forever to produce an apostiled version of la esposa’s birth certificate, and our residency paralegal being apparently overworked and particularly disorganized. On prior “border runs” (expatoise for the visa renewal process) we had taken short flights to Miami, Orlando, and Mexico City. This time, with the world mid-Omicron, we decided that a drive over the border was the way to go.

We’d intended to leave earlier, and be halfway to the border by 9AM; however, we’d been disorganized in the days leading up to the trip, and had spent part of the early morning digging through files for paperwork that would be needed for the upcoming day’s adventure. Also, we hadn’t planned to travel via San Isidro; however, we’d discovered late the previous evening that an exit permit was required to take a car out of the country. None of the english language blogs that describe the border crossing process had mentioned this, seemingly because most people walk (or are bussed) across the border, and possibly rent a car on the other side. Exit permits for cars fortunately are available same day, but the closest government registry office that provides them is located on the upper floor of a bank in San Isidro.

Truck caravans and macho pickups navigated, we arrived at the bank shortly before 10AM to find a line of people stretching around the block waiting to get inside and conduct their business. Extrapolating from prior experience, we figured that this was at least a 2 hour line, which put our chances of getting to our rental cottage (2 hours inside Panama) before dark in jeopardy. (My original plans had put us easily arriving by midafternoon - 2 1/2 hours to the border, 2 hours at the border, 2 hours on the other side - what could possibly go wrong?) Many in the line were brandishing umbrellas to protect themselves from the heat of the sun, already intense at this early hour. Fortunately, it turned out that the bank was simply late in opening its doors, and after around 10 minutes around half of the line was waved into the building by the guard on duty. After another 15 minutes or so, the same guard plucked us out of the line as the next customers of the registry office; only one of us was allowed to go in, however, so la esposa (possessing a better command of spanish) took the mission while I wandered off to stock up on food for the drive.

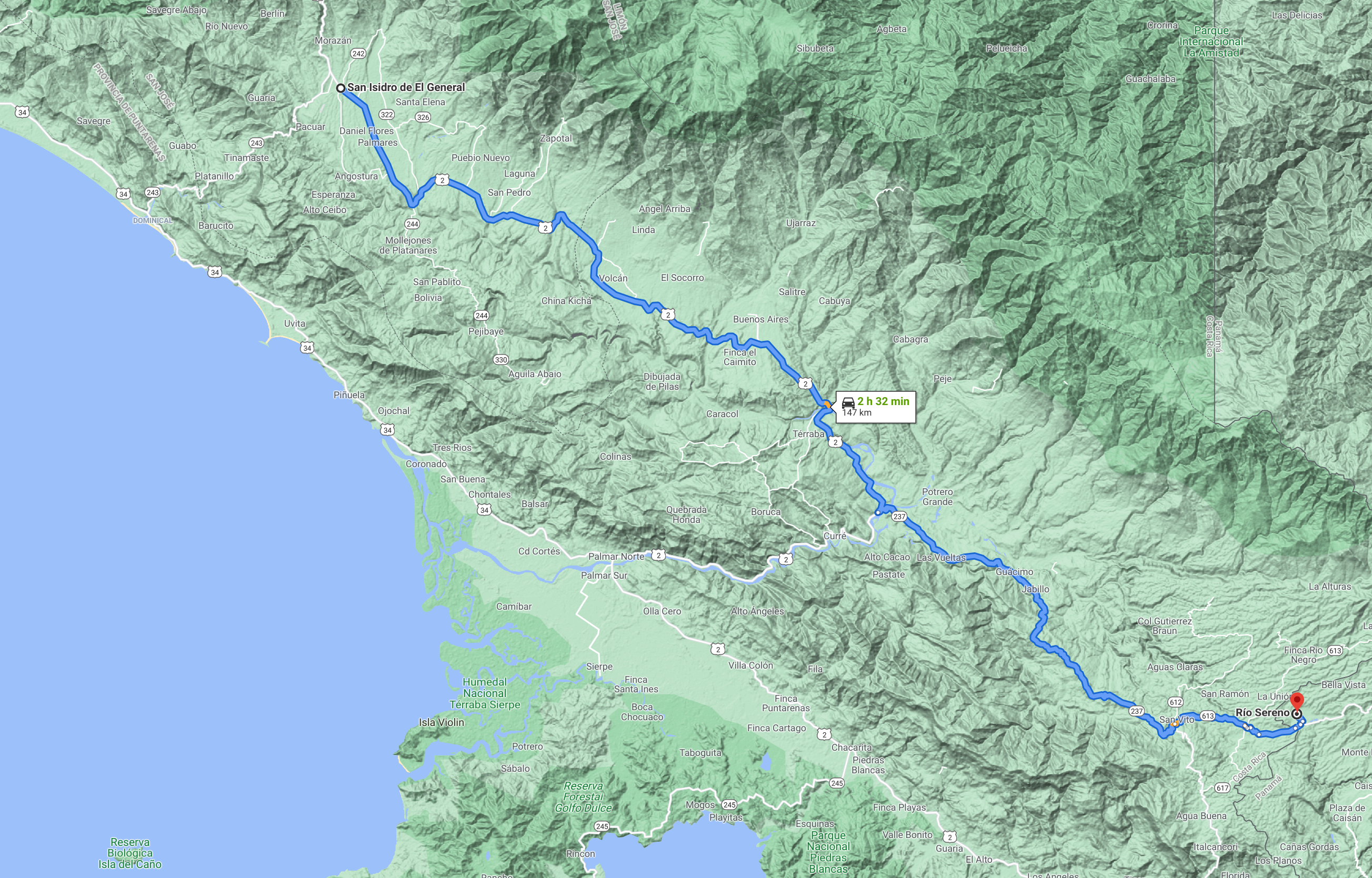

Back on the road by 11AM (and diets already thoroughly blown by the greasy deep fried empanadas I’d accidentally bought), we had an uneventful drive through the pretty agricultural valley and mountains that lie between San Isidro and Rio Sereno (a backwater border crossing, which we’d decided would be a less annoying town to make the crossing in than Paso Canoas, the primary commercial border town.) Costa Rica is known for being a country of many microclimates; whereas the rainy season hadn’t fully wound down on the coast (it being a La Niña year), parts of the mountains along the drive were parched, reminding us of Southern California. Crossing from one valley to the next, suddenly the arid soils gave way again to lush jungle and deep green grassy pastures. Closer to the border, enormous fields of pineapples stretched to the horizon, almost tinting the air with the intense blue-green of the foliage; giant jets of irrigation sprinklers blasted streams of water across the crop.

And then, a mile before we’d expected it based on el google’s markings, as we rounded a corner to pull up at a crossroads, here was the border. Ahead of us were three plastic bollards connected with (appropriately enough) boundary marking tape, blocking off a one lane driveway that passed between two metal mesh fences, and then another row of bollards on the other side. To the left were a cluster of uninspired concrete buildings, and to the right a minor hub-bub of shops, and a parking lot. We parked, and got organized.

At the border

Panama is on EST (perhaps to make it easier for tax optimizers in NYC and Miama to do business?), which we hadn’t accounted for, so having arrived not terribly behind ideal schedule, at 1PM Costa Rican time, it was suddenly 2PM. Still, though - we had only two things to do. First we needed to go to the Costa Rican migration office, and get stamped out of the country. Then we needed to walk across the road to the Panamanian migration office, and get stamped into the country. We’d prepared by printing out all of the paperwork that we’d need, so how long could this possibly take?

We walked across the street and down the block to the Costa Rican migration office, one of the concrete buildings. There was an Austrian family ahead of us in line, travelling the opposite way to us; they were efficiently dealt with in 5 minutes, and moved to the corner, where they huddled around the mother’s smart phone. We stepped up to the service window.

The immigration officer was perfectly pleasant. He took our passports, and then asked if we’d paid the $8 exit stamp tax. We had not; we’d heard it could be done in the migration office, and indeed he pointed us at a QR code that linked to a web application that allowed payment. Unfortunately, this border town is not served well by cellphone companies; neither of our Costa Rican sims were picking up any signal, but la esposa’s Google Fi sim had managed to connect to a tower in Panama, and had a weak but navigable signal. We brought up the site, painstakingly filled in the form, submitted payment, and got an error page.

The officer had told us that the other way to pay the exit tax was at the grocery store down the street, so we walked the two blocks to the store (there were actually several grocery stores, and our third attempt proved to be the charm) where the clerk entered information from our passports, took payment, and then took photos of the confirmation receipt using our phones for us to show back at the migration office. (It’s entirely possible she used the same website that we’d attempted to.) Back at the migration office, we handed back over our passports, showed the photos of the exit stamp tax receipt, and were rewarded with the circle of green ink on paper that denoted us as having legally left the country. The smile from the officer as he handed back our passports turned into a furrowed brow and a frown as la esposa told him “tenemos un carro” (we have a car); he yelled into the depths of the building for a colleague to come and handle this second transaction, necessary to authorize the vehicle to leave.

A woman came to the window, took our passports, and disappeared back into the void. After five minutes, she reappeared, handed back our passports, asked for some of the car paperwork (including the exit permit that we’d obtained in San Isidro that morning), and then said that she wanted to see the car. I left the office, walked back across the street to the parking lot, started the car, put it in reverse, backed out of the parking spot while turning, and collided with the rear end of a large white pickup truck.

El hombre piña

“Lo siento!” I exclaimed, as I hopped out of the car. It was true that his truck hadn’t been there when I’d started the maneuver, but I’d been distracted and hadn’t been paying full attention; it was more my fault than his. The panel over the rear wheel of la esposa’s car had been pulled off, the clips that were supposed to hold it in place having been partly broken. There was a moderate dent on his chrome bumper. Could have been worse.

In Costa Rica, when and if you get into a car accident you are supposed to leave the vehicles where they are, and wait for an agent from the insurance company to arrive. This will almost always take hours, especially if you’re in a backwater town, as we were; this may well be a deliberate strategy on the part of the insurance companies, as it encourages an informal negotiation and handshake in the case of a minor incident, like this one. However, in more serious accidents, often vehicles will remain in the middle of the road for hours, potentially blocking traffic, while the insurance agent is en route to the scene. I’d already by reflex pulled the car forward several inches after the initial crunch, so el hombre and I spent the first couple of minutes speculating about exactly what had hit what in order to cause the damage.

We were already running much later than planned, and the damage wasn’t significant enough to worry about. I figured he probably needed a new bumper, probably a few hundred bucks worth of repair. La esposa’s car had no real issues, aside from the panel clips, so probably was a cheaper repair. I only had a $20 bill in my wallet. We had $500 in cash in la esposa’s purse, but she was back in the migration building. I proposed that we swap details, and that I’d pay him online when I was back home. He understandably enough wanted to settle the matter in person, so I asked him how much he proposed. I didn’t want to suggest a number, since in negotiation it’s always better to let the other party anchor with a first number, and then come down from there. He hummed and hawed, and perhaps to delay while thinking about it told me about the organic pineapple farm that he owned.

In the meantime la esposa appeared, marching briskly up to our conversation. She’d gotten worried when I hadn’t returned within 5 minutes, imagining that I’d been kidnapped by border gangsters, and was alarmed at the transaction taking place. After she understood the situation, she brusquely asked “What do you want?”, and dug $150 out of the dashboard, where the cash had been all along. El hombre was a little offended by the type A turn in the transaction, and after she drove the car back to the migration office, turned to me and asked if she was angry with him, or with me. “Both, I guess?” I replied. He gave me a hug as we parted ways.

I walked down to the hardware store while she was concluding the car authorization, and bought duct tape. Back at the parking lot, we met the driver, Rafael, again. Now more friendly, he showed us photos of his farm while I taped the panel into position as securely as I could. He traded whatsapp details with la esposa, and invited us to lunch with his family when we were passing back through the area.

Entering Panama

One hurdle remained to enter Panama: the Panamanian migration office, across the street from the Costa Rican compound. Sitting out front at a plastic conference table were two lethargic middle aged ladies, alternating lazy attention between hand written form books on the table in front of them, and their phones. Two empty plastic single serving cake containers sat in the middle of the table, crumbs and singly-used plastic forks enclosed within - maybe it had been somebody’s birthday, or maybe it was just how these ladies liked to lunch. Their jobs evidently were to administer covid tests and/or validate vaccination cards; given that we had the latter, we were dispatched back down to the row of shops to get photocopies of the vaccination cards made. On return, our details were studiously written into the form books, and we were waved inside the building.

Stepping into the doorway, the hallway divided into two rooms. On the right were a cluster of paramilitary police, looking quite serious behind a high counter. On the left was a room with a row of desks and computers, with several plastic chairs in front of them for interviewees. We were the only travelers in the building. We entered the room on the left, and handed over our passports. During her interview la esposa disclosed that we were bringing a car into the country. “Tienes seguro?”, he asked - do you have insurance? We’d been aware that this was coming; we needed a separate policy issued by a Panamanian insurance company to cover our time in the country, as our Costa Rican insurance didn’t cover out of country travel. We were sent back to the row of shops again, this time to a shack precariously propped up between two more substantial buildings, where we were diligently provided with a temporary insurance policy. Back at the Panamanian migration office, we presented our new policy, had our pictures taken with webcams (mask, hat and glasses off), fingerprints taken, passports copied, and were dispatched back out into the world to go through customs (to get the car cleared.)

We weren’t quite sure where the customs building was aside from the vague “over there” we’d received from the migration officer when we had asked, so we pulled the car up to the plastic bollards with boundary tape, and waited for a couple of moments. Nobody showed up, so I got out of the car, walked back to the migration building, and asked the lethargic ladies, who pointed me at a building semi-residential in appearance in the block behind the fence. “I just walk over the border to it?” I asked in English, while making the international “walking” gesture with two fingers. “Si”.

I walked across the imaginary international line, and then down the garden path in front of the customs building. A woman greeted me at the window at the front of the building, and I asked if this was the right location to get the car’s entry approved. She affirmed, and I walked 20 yards back to Costa Rica to fetch la esposa and paperwork, leaving our car blocking the border entry. Back at the window, the customs agent sternly asked if we had photocopies of the car title and registration after we presented the original documents, and said that we’d need to walk back to the shops in Costa Rica to make copies. A few minutes later, after having entered many details into her computer, she relented on the threat and made copies using the photocopier that was right there on her desk, next to her computer. After around 25 minutes we were fully approved, and waved back to the car. A customs officer and the agent followed us; the officer removed the bollards from in front of the car, beckoned me to drive forward between the two mesh fences, and then to stop. The outside of the car was then sprayed with disinfectant, the bollards on the other side of the fences removed, and I drove the car over a speed bump and into Panama.

I was then instructed to open the trunk, after which the agent and officer looked inside our laptop bags, looked inside and then giggled at the contents of our cooler, and squeezed the outside of our backbacks to confirm that they contained clothes. “Listo!” We were officially approved. We’d seen no other cars crossing the border in the two hours that we’d been bouncing around. It was now just after 4PM.

A Man and a Plan

I drove forward into town; at this point we had no reception on any of the phones, and therefore no detailed directions to our Airbnb, having set up GPS to guide us only as far as Rio Sereno. El google was showing our location on the map, however, and we knew the location of the town we were heading for; we just needed to find the right road out of town, and then it would be a fairly straightforward journey to the cottage. I got in behind a big rig and a small line of cars, figuring that everybody would would be taking the one marked road on the map that headed towards civilization; after following them for around 10 minutes on a 1 1/2 lane road, however, the asphalt abrubtly gave way to gravel, where an obelisk sat in the middle of a small parking lot surrounded by a few shacks. The big rig drove through the parking lot and continued on the dirt road which left the other side of the lot; we pulled over and checked google maps again. It turned out that we were at a non-official border crossing a few miles out of town, and that had we continued would have been back in Costa Rica. Indeed, having parked on the wrong side of the obelisk, we probably had re-entered the country.

We turned around and worked our way back through town, this time picking up the correct road, and for the next hour and a half drove along narrow winding roads through the mountains, passing houses with neatly landscaped front gardens, bougainvillea spilling out of gateways, pretty fields, and neat citrus orchards full of rows of meticulously pruned trees. We saw frequent evidence of landslides, the asphalt having been washed out on various inset hairpins, and construction crews repairing slopes. Coming around one particular hairpin, we drove up to a police checkpoint, and paramilitary officers waved us down to check our identification and permits. Our previous visit to Panama had been back in 2018, and we’d encountered similar checkpoints then, presumably organized to curb the flow of drugs on overland routes.

Eventually, while cresting one particular mountain pass, we got a cell phone signal again, giving us enough time to enter the address of the cottage and get the remaining directions that we needed. The remaining drive to the cottage was uneventful; we arrived in the dark, and woke up the next morning to find a parched landscape in the shadow of a volcano, strong winds whistling through the scrubby trees. The cottage itself had been somewhat overbilled (as “luxury”) on airbnb, but it did the job, and we felt bad for the family, who had apparently begun construction right before the pandemic and run out of money before they could finish. Particularly amusing was the bathroom, built into the wasted space made by walling the steep pitch of the roof; it was so narrow that I couldn’t stand up straight, or sit on el bano without major contortions.

After a day of low key activity, the following morning we retraced our steps to the border to obtain the all important updated entry stamp, the purpose of the entire trip. This time we had to take the process exactly in reverse - first customs, then Panamanian migration, then Costa Rican migration. Had both the migration offices not been on break for lunch, we could have gotten everything done within 15 minutes. Lunch breaks included, the transaction was complete within 45 minutes, and we were back in Costa Rica by noon.

We spent the night at La Cruces Biological Station, a lodge run by a nonprofit, catering to university students and floppy khaki hat wearing bird watching touring groups, set in the middle of a 50 year old botanic garden, and just 25 minutes on the other side of the border. This turned out to be the highlight of the whole trip, with a relaxing setting and pleasant accomodations.

We returned home on Monday, adventure concluded. A lot of driving just for one entry stamp, but with advance knowledge of exactly which documents photocopies were required for, the border crossing wouldn’t have been too bad. Taking a car over wasn’t terrible either - obtaining the exit permit well in advance of the trip and figuring out how (if possible) to get the Panamanian insurance policy online would have cut down on most of the headache.