“Internationalization” is, roughly speaking, geek-speak for the process of supporting multiple languages on a website. For a company doing business in multiple countries, it needs to be done - otherwise you’ll risk losing the attention of people who don’t speak your development team’s native language. There are standards defined that specify what language to serve a website in to a particular user. So why do some of the world’s biggest sites get it wrong? Let’s take a tour of the landscape.

First of all, what is the standard? Let’s quote from the MDN article which describes the Accept-Language header:

The Accept-Language request HTTP header indicates the natural language and locale that the client prefers. The server uses content negotiation to select one of the proposals and informs the client of the choice with the Content-Language response header. Browsers set required values for this header according to their active user interface language. Users rarely change it, and such changes are not recommended because they may lead to fingerprinting.

This is pretty simple stuff. The user’s browser sets the Accept-Language header, based upon the operating system settings. This header is sent to websites to tell them what language to serve the site in. In other words, you tell your computer that you want everything to be English, or Dutch, or Spanish; your computer then passes that information on to websites when you connect to them, and you should get the website back in the language of your preference, if you are in their target market.

And yet, in the alternate reality that we all live in, if you take your laptop from one country to another then suddenly some websites will start serving you content in a different language, based solely on your location having changed. This shouldn’t happen, since the language preferences in your browser haven’t changed when you entered the new country. While clearly there is a general correlation between average audience language and location, it is not true to say that location equals language. It is in fact a fallacy to make that assumption.

The Settings

I did a lot of testing to see how widespread this issue is. A quick summary of my setup:

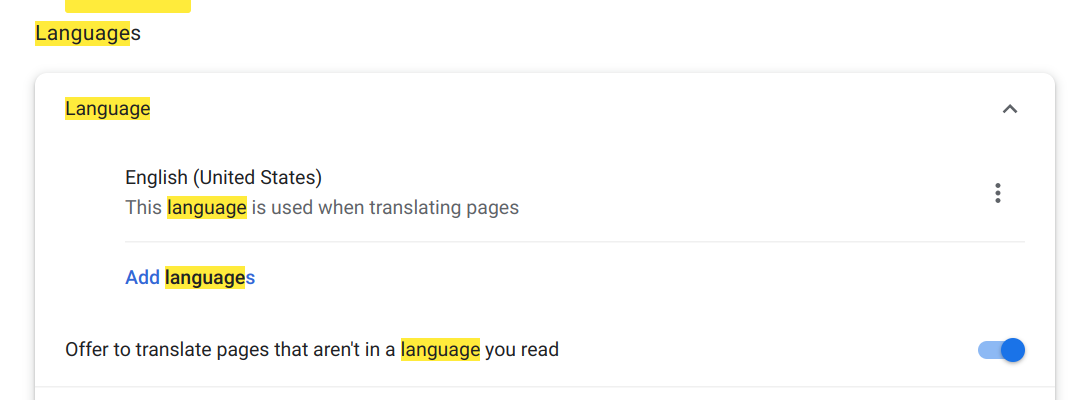

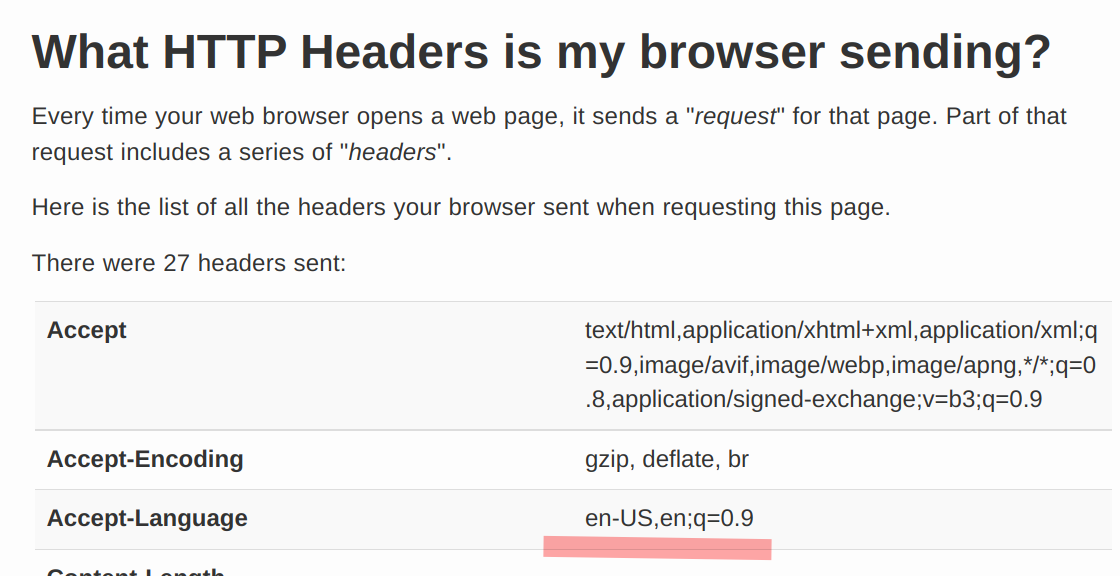

- In Chrome’s and Firefox’s browser settings, the only language I specify is English

- I live in Costa Rica

- My ISP connects to fiber that runs from Costa Rica directly to the west coast of the US

- My IP address geolocates to San Jose, Costa Rica (the capital city.)

Using the handy WhatIsMyBrowser.com I can see that the requested language is being sent as I specified:

Google Gets It Wrong

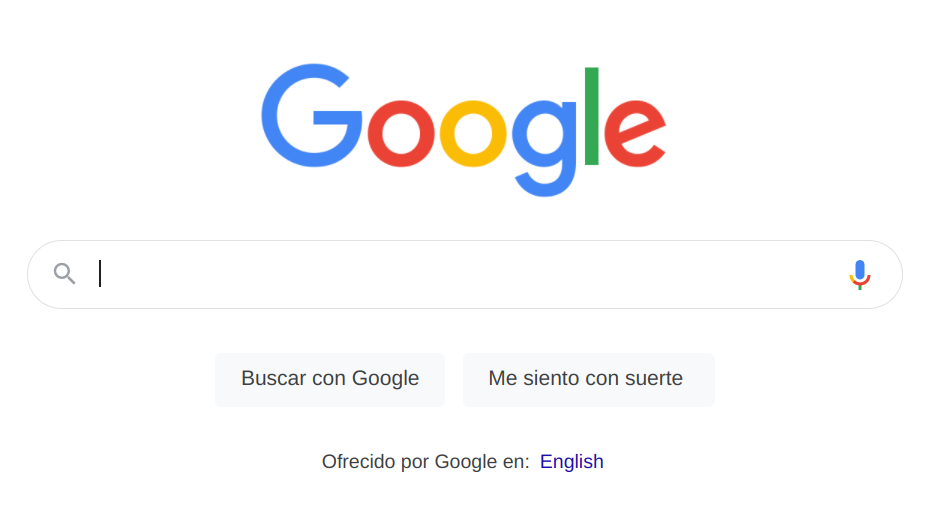

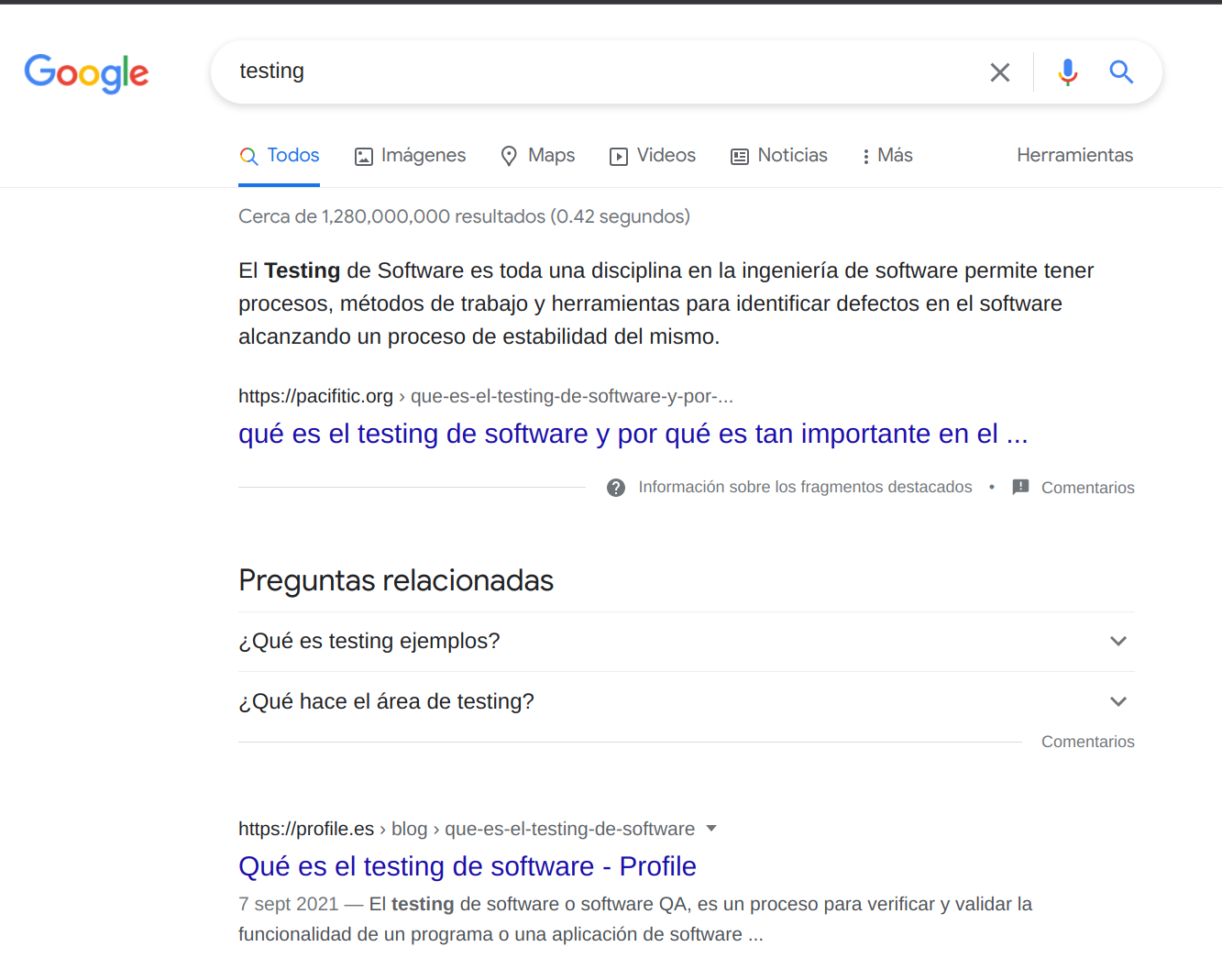

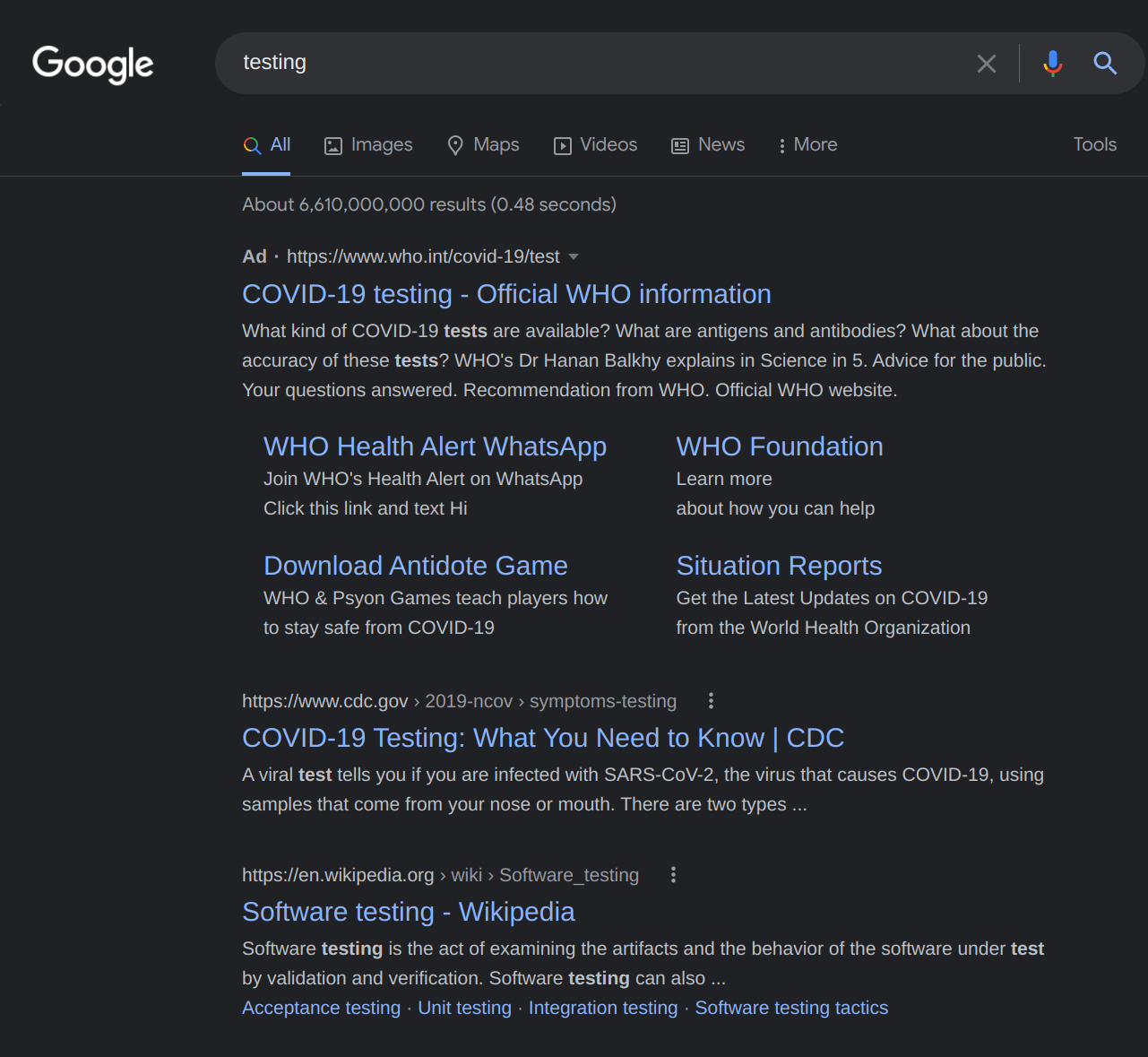

Google is the most prominent offender. If I’m signed in to my browser profile in Chrome, the search engine is served in English. No problem. The moment I try to access it from incognito, or Firefox, however, I get the Spanish language version of Google.

Bing doesn’t do this.

Neither do Facebook, Amazon, Instagram, Pinterest. Even Youtube (of course, a Google property) gets it right! (And yes, all of these sites switch to serving Spanish if I switch the browser language.)

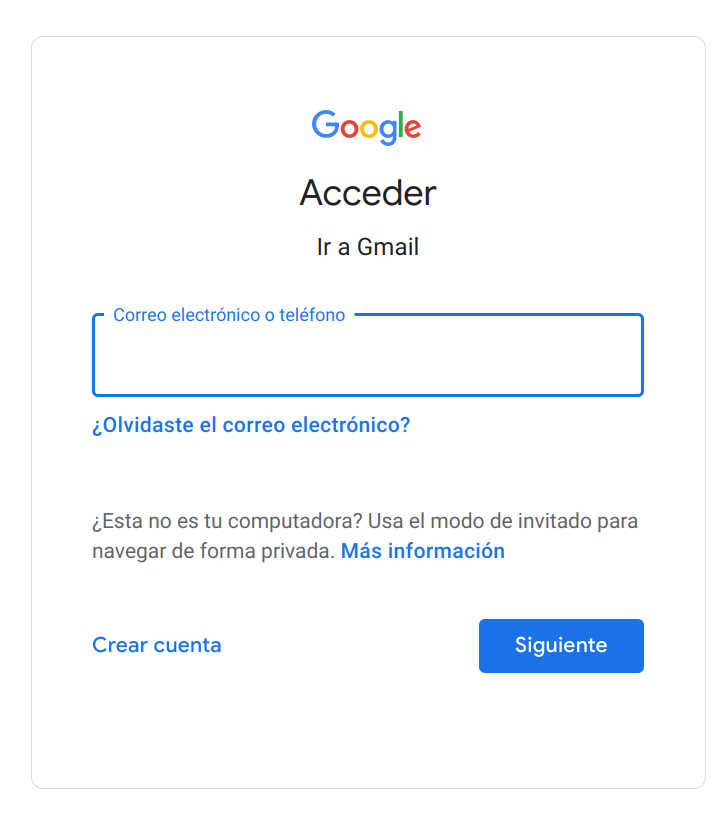

Google have the same issue on their auth service.

It gets even worse though. When I search Spanish language Google (which, remember, is the version of Google I get when I’m not signed into my profile, despite asking for English via browser settings), I get…wait for it…Spanish language results, which are completely different sites from those that I’d get had I searched English language Google.

Granted that one of these results is an ad, but presumably the reason that it didn’t show in the Spanish Google version is that they filtered me out from English language ads, doubling down on the location equals language fallacy.

Furthermore, as we all know, many users of the web just type site names into Google in order to navigate the web; the location bar is a weird mystery to them. If I search for Facebook in Spanish language Google and click on the first result, now Facebook is in the wrong language, because Google sends you to the localized version.

It does the same thing with the US embassy site (which serves in English from English Google, and serves in English if I navigate directly to it.) Might be a problem for travelers, no?

Or with Wikipedia (which, again, does the right thing if you navigate directly to it):

This also happens if I type “Facebook” or “US Embassy” directly into the location bar of Chrome (with Google as my search provider). Granted that this isn’t the end of the world between Spanish and English, but if you were in a country with a completely different alphabet, you might be totally lost. This isn’t a new problem with Google. I remember visiting France in 2017, and having the same problem then on my laptop which only hours before was giving me results in English.

Other Offenders

Google isn’t fully alone in this, although almost all startup sites (that I tried) get it right.

Microsoft

While we saw that Bing does the right thing, above, Microsoft is horrendously inconsistent. Microsoft.com and Microsoft365.com are wrong:

And yet Office.com is correct:

Xbox.com looks promising:

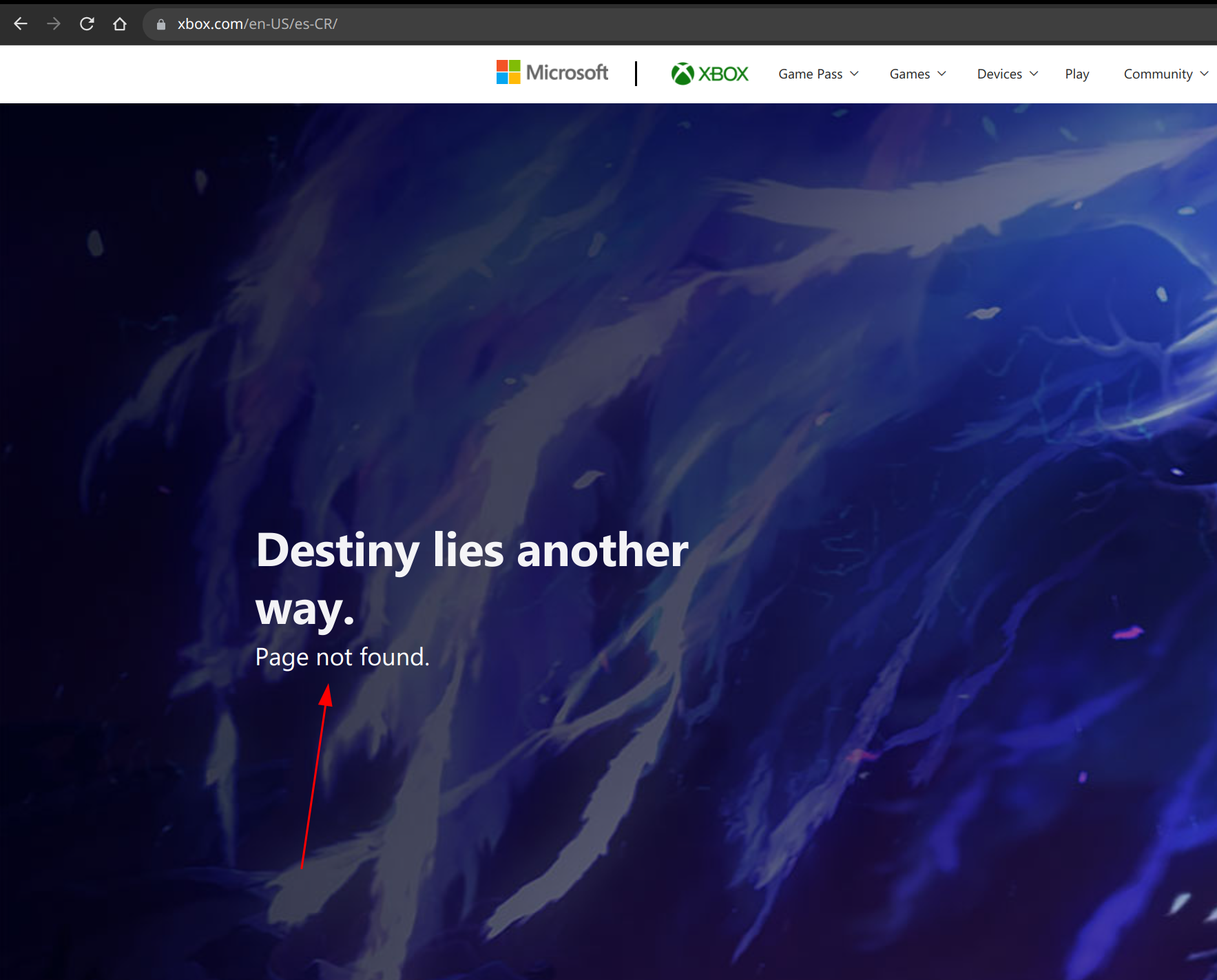

…but when I switch to Spanish it’s still served in English, AND it fails to find the main content page. (Note the es-CR in the URL; since I specified the language as “Spanish” rather than “Spanish (Latin America)”, that indicates that they’re geolocating.)

Yammer, another Microsoft property, hedges its bets. Main site content is based on Accept-Language, but they pop up a language chooser based on geolocation, just in case. This is justifiable.

Yahoo

Yahoo (remember them?) do it wrong.

EBay & Paypal

Both EBay and Paypal equate language with location. Of course they’re separate companies these days; but it’s an interesting commonality - maybe there’s some shared infrastructure deep in the codebase. Venmo and Cash.app both get it right.

IBM (vs Red Hat), Deloitte (vs Accenture)

IBM gets it wrong.

Red Hat on the other hand seems correct…

…but it turns out (when I switch language to Spanish) that they only got as far as internationalizing their cookie banner before giving up:

Deloitte wrong.

Accenture, despite their $50 billion in revenue, haven’t bothered to internationalize, and serve English content for both Spanish and English requests.

DHL (vs Fedex & UPS)

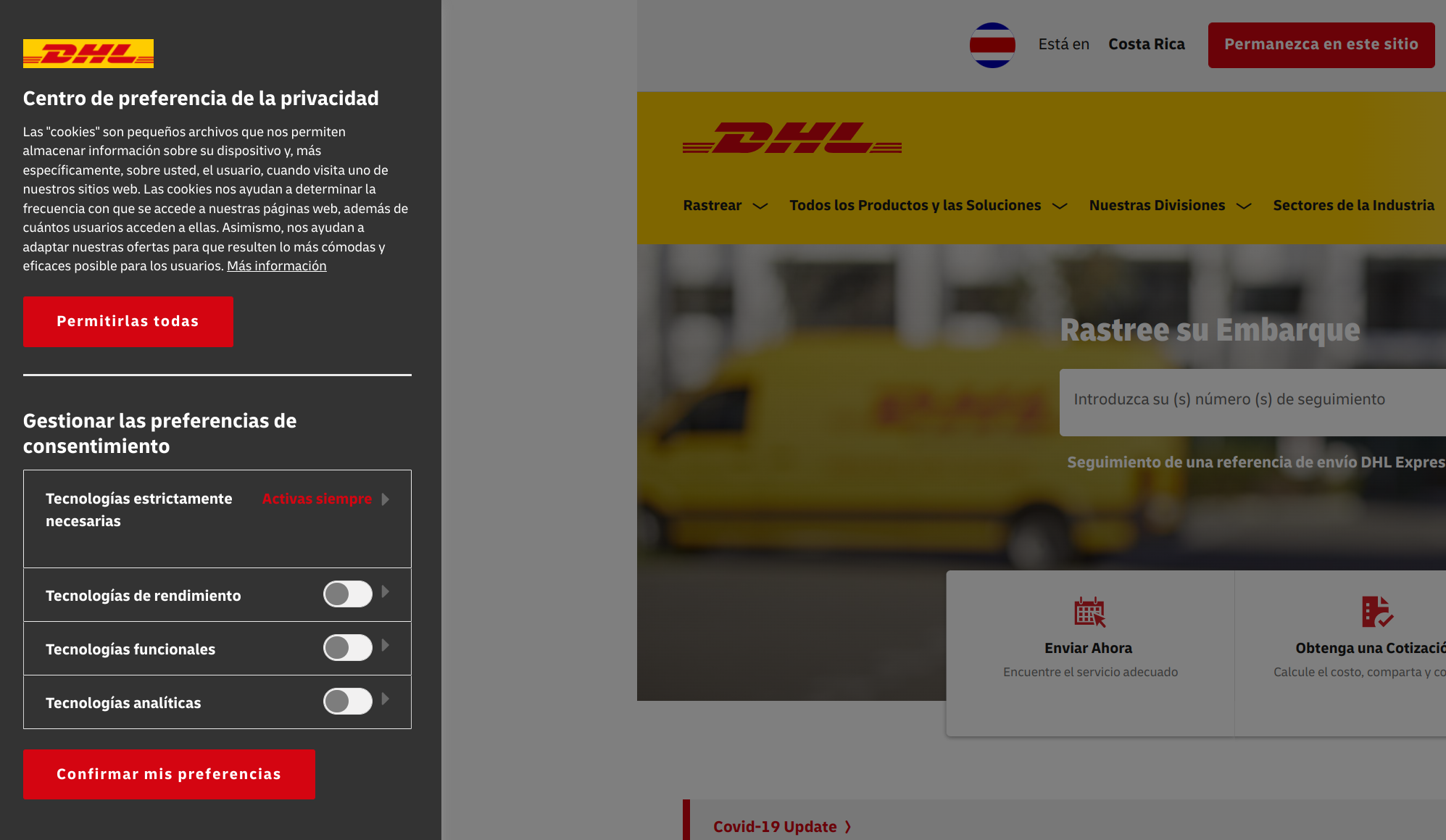

DHL wrong.

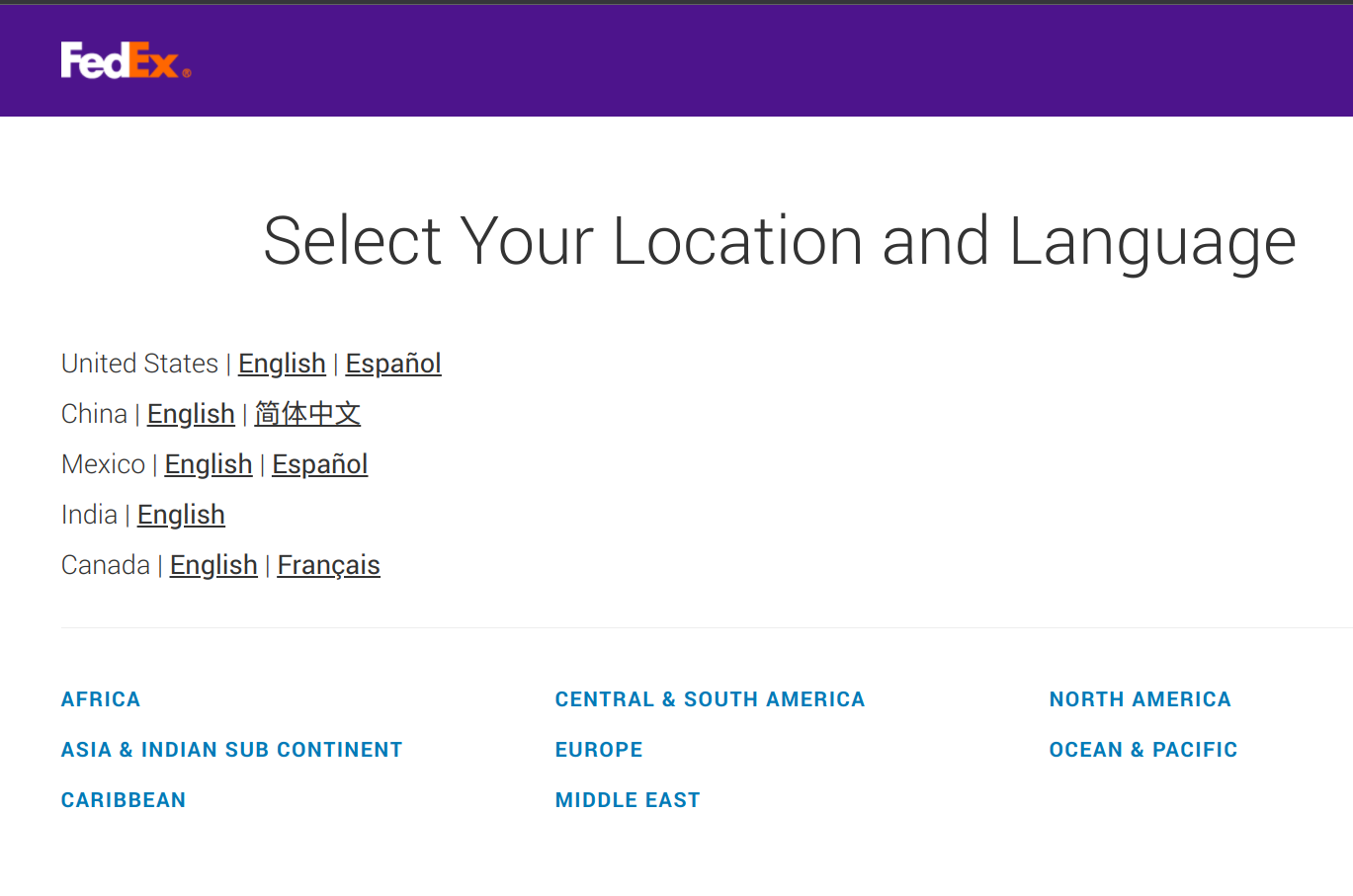

Fedex don’t trust browser settings, and always serve an English language page asking you to choose your locale. They also evidently don’t trust geolocation, so they have a crappy default selection of your location:

…as do UPS:

Walmart

Walmart, despite having a physical presence in Latin America, serve only the language of Freedom, no matter what browser langauge you request:

HBO Max

HBO Max of course is its usual half-assed dumpster fire. Despite the app being in English, it sends me Spanish language notifications, and some error messages appear in Spanish.

Netflix

For different technical reasons, Netflix gets subtitles horrendously wrong. My Netflix profile is set to English.

Let’s say I wanted to watch Parasite, an excellent Korean language movie, and need subtitles. Guess what:

Start watching Parasite in the US, and you’ll get English as an option under subtitles. On the other hand, Squid Game is fine.

This, Netflix support insisted, is due to the licensing of their catalog. Seems like a poor implementation to me though.

There’s another, more esoteric problem with subtitles. Suppose I’m watching a movie with some Costa Rican friends, and they insist that we watch in English (they are relatively fluent in English, don’t like dubbing, and also want to improve their English language skills). However, we turn on Spanish language subtitles to help them out on words that they don’t know. Halfway through the movie, there’s a scene between two Russian gangsters, with Russian dialog. If the Spanish subtitles weren’t on, you’d get subtitles in English covering the Russian dialog. But because you can only have subtitles in one language at a time, the English subtitles never show up, despite the movie playing primarily with English audio. Of course it would be ridiculous to have subtitles in two languages at one time, right? Right? Right?

Theories

So what’s the reason for this being done so badly in these various cases? I don’t have a slam dunk theory, but below are some possibilities.

Age of Website

Is it possible that the age of website is somehow correlated with a bad internationalisation implementation (e.g. using IP geolocation rather than Accept-Language)? This seems unlikely, given that HTTP 1.1, which introduced Accept-Language, was published in 1997.

Location of Servers

Truly international websites will have servers in different regions of the world. Through the magic of the internet, when you go to their domain, you get redirected to the servers nearest you. Those servers default to the language of the locale. I find this explanation plausible, but it’d certainly be a bug (since, again, it’s ignoring the Accept-Language header.)

Some Weird Audience Optimization

Microsoft and Google are big guns in tech; they don’t have any inconsistencies in their products and everything they do is deliberate, so they surely know what they’re doing here (slash s). Maybe statistics they’ve run prove that they get higher engagement by frustrated users scrambling around in an interface they don’t understand to find the god damned language switcher, and therefore the A/B models prove it’s the right thing to do. Or something like that.

Incentivizing Signing In

The company went to the trouble of creating user profiles in which you can set your language preferences. To encourage people to sign into their profile (so they can be tracked better), maybe it’s a deliberate choice to display the language based on geolocation? I don’t think this makes much sense, since if that were the case why wouldn’t the signed out version be deficient in ways that encourage sign-in when travelers were on home turf?

Org Too Big, Nobody Cares

You don’t put your best engineers on the task of internationalization. It’s a boring, routine task, and involves lots of boilerplate. Nobody’s getting a promotion over translating the site. Maybe it gets half-assed, issues missed in QA, and site launched. Maybe once launched into a new market, you care about the 95% of users who work in the primary language of the country, and that’s good enough. Everybody moves on. The support organization hears about the problem periodically, but they’re not allowed to talk to the development team, and their script says “this is deliberately based on your region”, so nothing ever gets back to decision makers in the organization.

Overly Specific Product Managers

Most product managers won’t know about Accept-Language. In Chrome, the Language setting is buried under “Advanced” settings (I guess it’s “Advanced” to speak something other than English), so it’s not unreasonable to not have known that you can set it in the browser. It’s easy to imagine a product manager who writes “Site language should be based on the primary language of the country” because they didn’t know any better, and a sub-par development team implementing to spec because they assumed the spec had been well though through.

Conclusion

If plausible reasons surface from discussion, I will update this post. Failing that, if you work at Google (or Microsoft), please fix this.

Update

I posted this on hacker news; the answer, at least for Google, seems to be:

I worked at Google in 2000, and I found this annoying too, so I asked about it. The official reason was that a lot of browsers defaulted to en-US, so Google effectively treats an Accept-Language of en-US as a no-op, and then it falls through to location-based. (I don’t agree with this rationale, and said as much, but there you have it.) Note that other values for Accept-Language are not ignored. I haven’t tried it myself, but I’ve heard some people say that setting their language to en-GB or en-CA works well. You can also use &hl=en-US, which always takes precedence.

- xenomachina https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=30642273